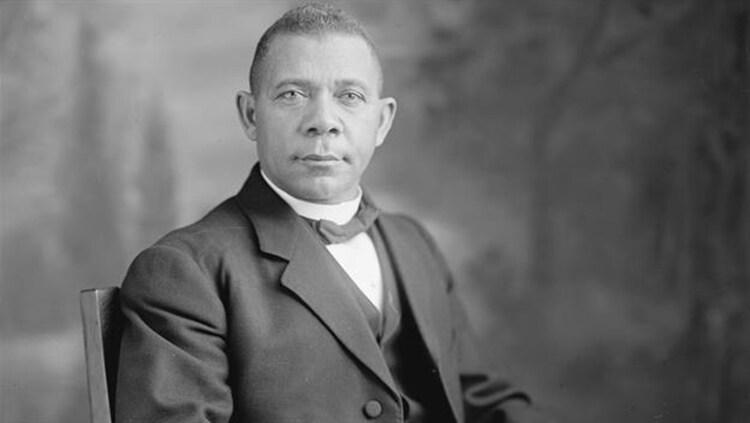

Based on Darrell’s recommendation on the 100th episode of the Just Thinking Podcast, I bought a copy of “Up from Slavery”, Booker T. Washington’s autobiography. I just finished the book and want to share a few things that stood out to me.

Washington was able to reach the most influential people in his lifetime in the USA and beyond. From conferences with and speeches before businessmen and senators, personal meetings and correspondence with Frederick Douglass, Andrew Carnegie, John D. Rockefeller, and Presidents Cleveland and McKinley, dinner receptions with ambassadors and statesmen in France and England—at one of which he met Mark Twain—and tea with Queen Victoria. I was astounded by his reach and the response of his audience to him personally and his speeches.

At the same time, Washington’s humility and grace were astonishing. For example, he described his white, absentee father in this way:

Of my father I know even less than of my mother. I do not even know his name. I have heard reports to the effect that he was a white man who lived on one of the near-by plantations. Whoever he was, I never heard of his taking the least interest in me or providing in any way for my rearing. But I do not find especial fault with him. He was simply another unfortunate victim of the institution which the Nation unhappily had engrafted upon it at that time.

He also had pity, not anger or hatred, towards those who would hold animosity towards anyone because of his skin color. Talking about President Cleveland, he wrote:

Judging from my personal acquaintance with Mr. Cleveland, I do not believe that he is conscious of possessing any colour prejudice. He is too great for that. In my contact with people I find that, as a rule, it is only the little, narrow people who live for themselves, who never read good books, who do not travel, who never open up their souls in a way to permit them to come into contact with other souls—with the great outside world. No man whose vision is bounded by colour can come into contact with what is highest and best in the world. In meeting men, in many places, I have found that the happiest people are those who do the most for others; the most miserable are those who do the least. I have also found that few things, if any, are capable of making one so blind and narrow as race prejudice.

In today’s context, I would add that this goes for all race prejudice, no matter which direction.

Probably the main theme of the book is Washington’s focus on education, by which he means industry and not merely book learning. In the context of seeing paintings by African-American painter Henry O. Tanner, he repeated his thesis:

My acquaintance with Mr. Tanner reinforced in my mind the truth which I am constantly trying to impress upon our students at Tuskegee—and on our people throughout the country, as far as I can reach them with my voice—that any man, regardless of colour, will be recognized and rewarded just in proportion as he learns to do something well—learns to do it better than some one else—however humble the thing may be. As I have said, I believe that my race will succeed in proportion as it learns to do a common thing in an uncommon manner; learns to do a thing so thoroughly that no one can improve upon what it has done; learns to make its services of indispensable value. That was the spirit that inspired me in my first effort at Hampton, when I was given the opportunity to sweep and dust that schoolroom. In a degree I felt that my whole future life depended upon my thoroughness with which I cleaned that room, and I was determined to do it so well that no one could find any fault with the job. Few people ever stopped, I found, when looking at his pictures, to inquire whether Mr. Tanner was a Negro painter, a French painter, or a German painter. They simply knew that he was able to produce something which the world wanted—a great painting—and the matter of his colour did not enter into their minds.

The lengths to which Washington himself and his later students went to gain such an education are admirable and foreign today. From traveling about 500 miles at age 14 on his own, with little money and needing to find odd jobs on the way, to sleeping in unheated tents in the dead of winter without complaining, the drive to learn was strong. These are the passages I wanted to read to my children to instill upon them the importance and value of education, but I realized that I would also benefit from adjusting my own attitude toward hard work and sacrifice by his example.

Once established at Tuskegee, he wrote about his routine and productivity to accomplish the tasks before him:

I have a strong feeling that every individual owes it to himself, and to the cause which he is serving, to keep a vigorous, health body, with nerves steady and strong, prepared for great efforts and prepared for disappointments and trying positions. As far as I can, I make it a rule to plan for each day’s work—not merely to go through with the same of daily duties, but to get rid of the routine work as early in the day as possible, and then to enter upon some new or advance work.

Work was not just something worthy to engage in, but something to be totally mastered:

I make it a rule never to let my work drive me, but to so master it, and keep it in such complete control, and to keep so far ahead of it, that I will be the master instead of the servant. There is a physical and mental and spiritual enjoyment that comes from a consciousness of being the absolute master of one’s work, in all its details, that is very satisfactory and inspiring.

This attention to detail showed itself in the excellence of work at Tuskegee in general. Agriculture and brick making, to mention just two, were practiced so well that the expertise and products of the Institute were in high demand.

In his speeches, Washington discussed the “progress of the Negro since freedom”, but this seems to always be in the context of continuing segregation. It sounds like African-Americans had to start over from scratch, assisted for the most part by the rest of the country, but separately nonetheless. In his words, “[i]n all things that are purely social we can be as separate as the fingers, yet one as the hand in all things essential to mutual progress.” It must not have occurred to him that joining traditionally white institutions could have been an option; something that is obvious to us today but the culture did not allow or encourage then. Despite this, his attitude was not one of victimhood, but opportunity. He made the most of what he had (or didn’t have, considering how much money he successfully raised for the Institute!) within the boundaries of the culture at the time, while advocating for progress and change.

More can be said about Washington and his life, but I purposefully leave it to you to explore. I would heartily recommend you take the time to read this short autobiography. Washington was a great model of Christian character, full of grace, humility, love, and diligence. I know I would do well to imitate much of his behavior and attitude.